Antarctic Penguins Stymied by Extreme Climate Events

New research involving CICASP's Andrew MacIntosh pits penguins against extreme environmental conditions during the 2013-2014 breeding season at Dumont d'Urville station, Adélie Land, Antarctica. This research was published in the journal Ecography.

Loss of a generation

"Among the outcomes of the drastic changes affecting the Earth’s ecosystems, nothing is more telling than a complete failure in the reproductive success of a sentinel species: a ‘zero’ year" writes Dr. Yan Ropert-Coudert, lead author of the paper and Director of Research at the CNRS-University of Strasbourg's Pluridisciplinary Institute of Hubert Curien (IPHC). Of the 30,000 or so breeding pairs of Adélie penguins living on Petrels Islands, none managed to successfully fledge any chicks, despite a hatching success of roughly 50%.

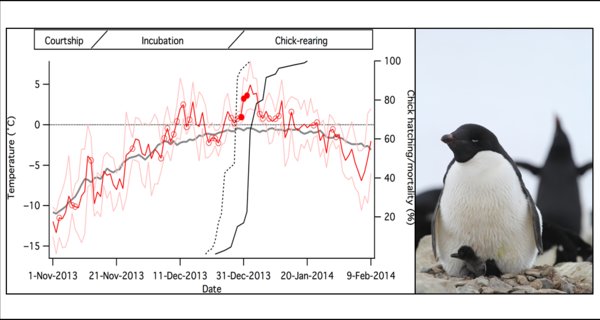

The team at DDU station, which included Dr. MacIntosh, monitored the colony of penguins over the Austral summer, which is the breeding period of the Adélie penguins that return there each year in October. The first sign that things were not as they should have been was that the year 2013 saw the greatest sea-ice extent around the Antarctic continent since 1979. Meteorological data from the station showed that autumn and winter 2013 were among the coldest since recording started in 1956. This contributed to the problem significantly, for when the katabatic winds that would normally blow from the continent northward and sweep the near-shore sea-ice away did not come, penguins were left with day-long hikes over 40 km away from the colony to reach open water and suitable foraging zones.

Exacerbating the problem were the unusually warm summer temperatures and frequent occurrences of rain, an unusual and in the end extremely unwelcome phenomenon in the area. Penguin chicks, which are so well adapted to the cold and dry desert-like conditions of East Antarctica, could not manage the odd thermoregulatory conditions now facing them: 49% of chicks died following a rany period that occurred just at the turn of the new year.

Complete breeding failures are extremely rare events in any environment, but the authors are cautious as to the interpretation of these results. Extreme events such as the one reported here can have direct repercussions for many species, but scientists don't yet know how cascading effects might also disturb the wider sea-ice dependent food web. In the paper, Dr. Ropert-Coudert posits an important question of the zero-year: "What will be the long-term effects on other species and trophic levels of the regional ecosystem?". Understanding the nature, frequency, and consequences of such events are central to the management and conservation of this remote yet crucial ecosystem.

This work was supported by the French Polar Institute Paul-Emile Victor (IPEV), the Terres Australes et Antarctique Françaises (TAAF) and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF).