Japanese macaque adaptations to environmental changes

A new study published in the American Journal of Primatology has shown that hormonal responses in Japanese macaques can be related to their adaptation to stressful conditions.

The study, led by PhD student Rafaela S. C. Takeshita, with affiliations to the Section of Social Systems Evolution, the Leading Program in Primatology and Wildlife Science and CICASP, involves the use of non-invasive methods to measure glucocorticoids (GC) and dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate (DHEAS) – two important adrenal steroids – from fecal extracts. This technique allows researchers to investigate stress in captive and wild animals without restraint or anesthesia that would otherwise confound the results.

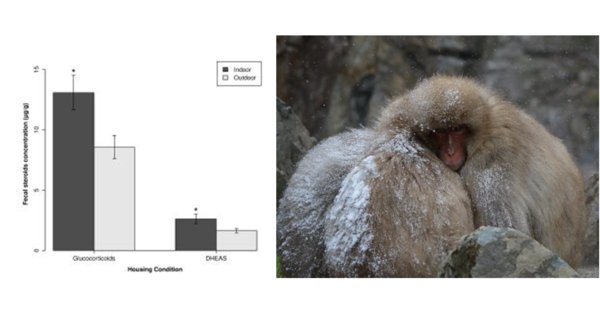

Previously, Takeshita and collaborators found that DHEAS decreases with age in Japanese macaques living in an outdoor enclosed social group. In this new study, they further showed that this association is more evident in individuals living in single cages, which might indicate that the environment can also influence adrenal hormones. Furthermore, the Japanese macaques living in a solitary, small indoor cage had higher levels of both GC and DHEAS than those living in an outdoor social group, suggesting a response to the stressful conditions in the indoor single cages. This is highlighted poignantly by a special case in which a female that was moved from her social group to an individual cage exhibited a peak of both adrenal hormones 10 days after relocation, and gradually showed a decreased in these levels thereafter.

The study also revealed that Japanese macaques living in the outdoor group had higher GC concentrations during the winter mating season than the spring birth season. A negative association between GC levels and temperature suggests that GC increases during winter months as an adaptation to “cold stress”. These findings can be one of the keys to understanding how Japanese macaques can survive in such a harsh, cold environment. Furthermore, this information can be used to improve the management and welfare of captive groups, and to monitor stress levels in wild and free ranging populations.

The study was conducted at the Primate Research Institute, Kyoto University in Japan, and it was financially supported by Nippon Zaidan and institutional funds from the Primate Research Institute.

For more information, the article can be found at DOI 10.1002/ajp.22295.