Red lips reconsidered

You know Valentine's Day is right around the corner when you step into your local grocery store and are immediately surrounded by an overload of red boxes and ornaments.

While other customers are deciding what to buy for whom, many of our scientist friends from PRI like to ponder on what genes enable us to taste the bitterness in chocolates, or why humans associate red colors with romantic intentions. Our colleague Dr. Lucie Rigaill is one of them (although she also enjoys eating chocolates): Dr. Rigaill has been studying the potential roles of naturally red skins (think lips and cheeks) in sexual signaling in humans and other primates. Her research was recently published in the journal Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, and so we were especially eager to hear from her about the secrets of the red color.

CICASP: Thinking beyond the cultural aspect of our attraction to red, how much biological evidence is there that males are attracted to reddening of skins in humans and other primates?

Rigaill: The “Romantic Red Effect” hypothesis proposes that red ornaments increase women’s attractiveness. Several authors have investigated such an effect, arguing that, in primates, the red skin coloration of the female genitals attracts males. So, you can find multiple papers claiming a red effect in humans. But more recently, researchers are criticizing these results as well as the Romantic Red Effect hypothesis, mainly because of methodological biases but also because of the theoretical framework. In fact, there is very limited evidence* that males are attracted to female red skins in non-human primates. That's probably because this has been a relatively understudied topic compared to the link between the red coloration of males and sexual competition.

*See: Dubuc et al. (2016) Who cares? Experimental attention biases provide new insights into a mammalian sexual signal, Behavioral Ecology 27:68–74; Higham et al. (2011) Familiarity affects the assessment of female facial signals of fertility by free-ranging male rhesus macaques, Proceeding of the Royal Society B 278:3452–3458; Peperkoorn et al. (2016) Revisiting the Red Effect on Attractiveness and Sexual Receptivity: No Effect of the Color Red on Human Mate Preferences, Evolutionary Psychology 14:1–13.

Red faces are prominent features of some primates, such as this Japanese macaque. [Photo credit: Lucie Rigaill]

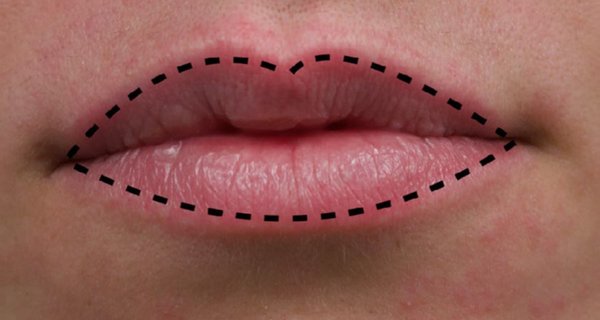

CICASP: In your study, you carefully tracked and analyzed the colors of lips and cheeks in women over their menstrual cycles to test the idea that those skins become redder or darker to signal ovulation (and attract potential mates). First, can you tell us why you decided to look at cheeks as well as lips?

Rigaill: I wanted to investigate if humans shared with some non-human primates a colorful red trait that was involved in sexual communication—studying the lips was thus obvious. But previous papers on this topic looked instead at cheek coloration. Cheeks are highly vascularized (though not as much as the lips) and because they are located just below the eyes, which gather most of our attention when we look at other people's faces, they could be a good candidate to examine. But cheek coloration is sensitive to emotional (e.g. embarrassment) and physical (e.g. heat) triggers. So, to be able to compare my results with those of other studies and also to be more conservative, I looked at lips and cheeks simultaneously.

CICASP: Interestingly, your result shows that women do not signal ovulation by reddening of cheeks and lips, and although lips become darker around the time of ovulation, the change is so subtle that it is probably not detectable by casual observers in real life. How do you interpret your findings?

Rigaill: So far, what I have collectively found is that neither humans, nor Japanese macaques, nor olive baboons use red coloration to signal ovulation—that phenomenon has been observed in only one primate species, the rhesus macaques. Humans may have other traits indicative of ovulation, like baboons, or they may not clearly signal their ovulation, like Japanese macaques.

Right now, it is difficult to assess which trait or combination of traits may signal ovulation to other individuals in humans because most studies to date have focused on whether men can discriminate between the facial conditions or odors of women during vs. outside of their ovulatory periods. But few of these studies have asked the important first question: Do the traits, such as the symmetry of the face or the composition of the odor, vary according to the probability of ovulation?

There is still a lot we don’t know about sexual signaling in humans and non-human primates to understand why some species clearly signal fertility while others don’t. This variability in function is likely the result of both ecological and social constraints inherent to each species, such as the availability of energy sources that are needed to express and maintain signals, the degree of sexual competition between females, and the degree of male harassment. These factors may determine the trade-off between signaling and concealing ovulation from the perspective of individual females.

There is a fair amount of variation in the darkness of lips among individuals (represented by the lines in the graph above), but individuals show little change over time. [Figure courtesy of Lucie Rigaill]

CICASP: So, if not for sexual signaling, why are lips reddish, and is there anything else that's special about our lips?

Rigaill: Good question. I have no idea to be honest! Well in fact, lips are highly vascularized so they appear darker, not especially redder. So, depending on the skin tone, the lips can appear more or less dark, red, pink, and so on. What I found more intriguing is the fact that humans have particularly well-developed lips compared to many other species of primates and animals in general. Could it be due to an important pressure from social factors? After all, lips play essential roles in our daily social life: they convey messages (vocalization and facial expressions in non-human primates, language in humans) and are a ‘tool’ used in social bonding (through grooming or kissing) for example.

CICASP: What does your research imply about the use of red cosmetics in humans?

Rigaill: If research on sexual signaling would affect the cosmetic business, then, I think that big branches should start selling and promoting red cosmetics for men! Red has been associated with social status, with the ability to win a fight or to secure a harem in primates*. So far, there is more evidence that red plays a role in males' attractiveness and their mating and reproductive success, than there is for females. Like for birds, it may be time for males to show some colors!

*For more on this topic, see: Setchell (2015) Color in competition contexts in non-human animals, in Handbook of Color Psychology (eds A. Elliot, M. Fairchild, & A. Franklin, Cambridge University Press) and Grueter et al. (2015) Sexually selected lip colour indicates male group-holding status in the mating season in a multi-level primate society, Royal Society Open Science 2:150490.

CICASP: [laughter] Good to know! Finally, where would you like to take your research next?

Rigaill: I’m generally interested in sexual communication, that is, behavioral, visual, auditory, and olfactory signals that play roles in mating strategies. As I said, there is still so much we don’t know about primate sexual communication and how it affects their socio-sexual lives. There is so much more to explore, it’s quite exhilarating when you think about it!

The biggest step would be to explore more of the two neglected aspects of primate sexual communication—female competition and male mate choice—because, historically, studies have almost exclusively focused on the opposites: male competition and female mate choice. For example, do females pay attention to other females’ signals and adjust their communication to win mates over their competitors? And do males choose to mate to increase their short-term reproductive success or are they more selective and strategic than we think, in order to increase their long-term reproductive success? These are the questions that drive my research.

Lucie preparing samples for analysis at PRI, and fully signaling her passion for science [Photo courtesy of Lucie Rigaill]