Ask Chimpanzees: What (if anything) is wrong with these pictures?

This time of the year, if you are hiking on a snowy mountain and see what appears to be a Yeti walking towards you, you should probably be alarmed and call the appropriate authorities (sorry, PRI doesn't have Yeti experts!).

You—and we humans—have this ability to visually recognize humans versus non-humans because, in our heads, we have an 'image' of what a typical human body looks like. Dr. Gao Jie, a PRI alumna (and our former teaching colleague at CICASP) who is now a JSPS Postdoctoral Fellow, wants to know whether that's unique to humans. To answer that question, she studies one of our closest evolutioanry relatives, the chimpanzees. Her new paper on the subject was just published in the journal Animal Cognition, so we invited her to discuss her latest findings and, more generally, what it's like to study chimpanzees at PRI.

CICASP: The main goal of your research is to find out whether chimpanzees have "body representations". Can you explain what that means, and why it's important?

Gao: In my article, what I mean by "body representations" is basically visual representations of bodies. In humans, for example, we can discriminate whether an animal is a human or a non-human animal, based mainly on visual cues. We use bodies to do everything, including social communication. We have pointing gestures to deliver information, and other bodily gestures to express intentions and emotions.

The understanding of what typical bodies look like is important for our daily life. Also, when a body looks strange, it might show injury and the need for medical care. In humans, we have this body representation. Bodies convey a lot of social information for chimpanzees, too, and they also use visual cues extensively. My colleagues and I wondered if chimpanzees also had body representations of chimpanzee bodies. Studying chimpanzees will also help shed light on the evolution of visual representations of bodies.

CICASP: Oh, I see. Being able to tell apart humans from other animals by looking at them feels like such a natural ability that I, as a human, have never really thought about it! Why has it been difficult to study this with chimpanzees? And what enabled you to undertake this study?

Gao: I think using traditional methods—such as face-to-face experiments, or touchscreen cognitive tasks—can tackle this topic as well, but indirectly. For example, we can test chimpanzees' reactions to atypical bodies, but it won't be that direct and accurate, compared to the eye-tracking method we used in this study: we could know where exactly they were looking at, when presented with various bodies. Another difficulty is that many previous studies have touched this topic, but there were too many cognitive processes at play—like imitation tasks using bodily gesture—so it was difficult to know exactly how they represent bodies.

Eye-tracking techniques help a lot in this topic. It enabled us to see where chimpanzees' gazes were and how long they looked at each place. We could examine their attention to various body pictures and know whether they paid special attention to strange body parts or not.

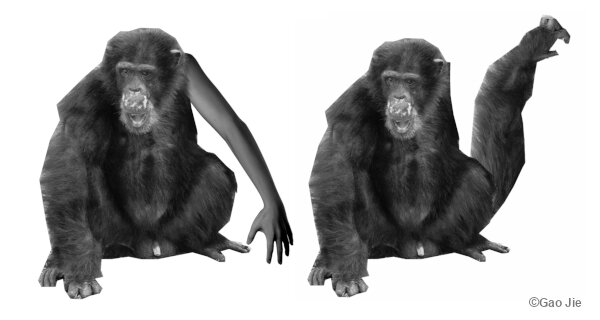

CICASP: So, you showed digitally-altered images of chimpanzees to our chimpanzees at PRI, and using an eye-tracking device, you monitored their gazes to learn if they paid more attention to unnatural body constructions [Images B–D below]. What challenges did you encounter during this study?

Gao: With 480 trials involving 6 chimpanzees, it took me several months to complete the task. One thing I did not expect was that the chimpanzees looked at other places instead of the screen during the task...so we covered the setting with a black cloth. It still happened, but it was somehow normal in chimpanzees. Their gaze is faster than humans, so they probably lose interest for the pictures after some time.

These images were separately presented to chimpanzees, and the levels of their attention were gauged. Image A is the original photo (= control), and Images B–D have been digitally altered. Note Image D shows a human arm attached to what is otherwise a chimpanzee body. [Image Credit: Gao Jie; original photos courtesy of Kumamoto Sanctuary, Kyoto University]

CICASP: The results of your experiments show that the chimpanzees noticed something was wrong when they were presented digitally altered images of other chimpanzees with human limbs [Image D in the figure above]. Were you surprised by this finding?

Gao: Not really. Chimpanzees can discriminate themselves from other animals, and they showed some evidence of body representation in my previous experiments examining body perception, so in theory it was expected that they notice the strange parts on chimpanzee bodies.

CICASP: On the other hand, when the same chimpanzees were shown digitally-altered images of other chimpanzees in which the limbs were attached to unnatural positions [Images B & C in the figure above], it was less clear whether they detected something wrong with those images. Can you explain what that means?

Gao: I think the human part might be easier for them to detect, because the fundamental looks are different from chimpanzee body parts as well (e.g., they are smooth). Still, they showed a tendency to look longer towards the misplaced arms and legs [image B in the figure above], compared to control, suggesting they might know that they are strange. We may need to conduct more trials to test this futher.

CICASP: I wonder if advances in 3D virtual visualization technology will allow experts like you to explore these topics further in the near future?

Gao: Absolutely. I think the new technology will allow us to have more types of visual stimuli to be used in the experiments. It is exciting to think about using a 3D atypical chimpanzee body and see how they react to it. But, of course, we need to carefully consider the ethics of such experiments first.

CICASP: You have spent several years both studying and taking care of chimpanzees at the Primate Research Institute of Kyoto University. What is the number one thing you want the general public to know about chimpanzees?

Gao: Chimpanzees also can catch a cold, and when they do, they eat their runny nose...

Ok this is a joke (but it's true!). I spent a lot of years observing them and working with them. Chimpanzees groom each other, play with each other, fight with each other. The alpha male always waits for all members before they come down for dinner. Mothers do not actively give food to their young, unlike humans, but they are tolerant of the kids taking their food. The babies have spontaneous smiles in their sleep, like humans and monkeys. Mothers lift up their kids for play, like we see in humans. They make alarm calls when they see snakes. They make food grunts when they see good food.

There are so many interesting things about chimpanzees, and it is so difficult to pick just one. Now the readers know many!

Chimpanzee Ai (left) with Dr. Gao Jie (Right) at the Kyoto University Primate Research Institute [Photo Credit: Gabriela Melo Daly]